A story: Not for the Ophidiophobic

I had taken my customary afternoon swim in the sacred pool near our campsite, and was sitting on shore drip-drying and chatting with colleagues. I looked up, and from a tad downstream, on the opposite shore, Alex caught my eye and beckoned me to come over. He was looking intently at something in the forest on shore, so I dove in excitdely and waded across the rocks and through the riffles to join him. “What did you find?” I asked, full of wonder. “A death adder,” he relpied, not in the least nonplussed. “You got me back in the water to get close to a @$#!% death adder?!?” I incrudlously, and indecorously responded. Alex proceeded to explain that though they are the fourth most deadly snake in the world, and there is no antivenin for their polyvalent venom, they are slow moving, non-aggressive reptiles that rarely kill humans. Much appeased (not) I apologized for my vulgarity (I never heard Alex utter profanity in the two weeks I spent with him) and, quite timidly, gained purchase on a branch and peered down at the small leaf brown animal. Wading back across the stream, I was overtaken by Alex who had to “run and tell the others.” In short order, Alex returned with Collin and Steve, and most of the rest of the team trailed, cameras in hand. Alex and Steve carried snake-catching tools.

The boys romped through the forest at the edge of the stream, looking to me like 8-year old boys catching frogs (or themselves catching anything with a backbone), until they successfully held a pillowcase full of snake. They worked their way back across the stream (Collin and Steve each lost a flip flop, an inadvertent sacrifice to the river gods as thanks for their good fortune) and handed the bag to me.

Back in camp, Collin double-bagged the quarry, gave it an appropriate hazard warning label, and hung it (where else?) at the front of the kitchen tent where it remained over night.

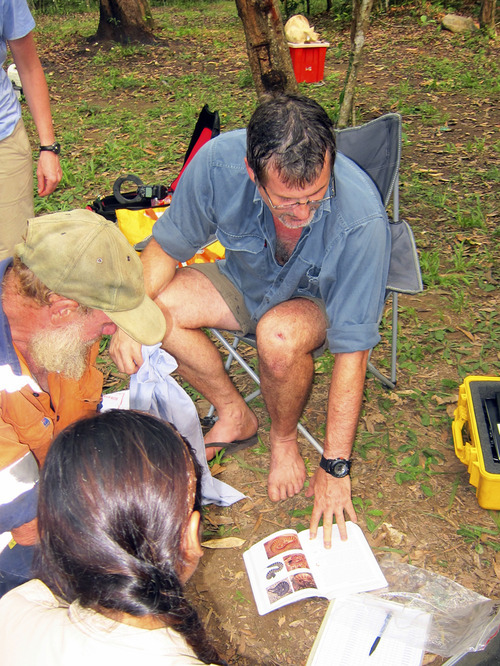

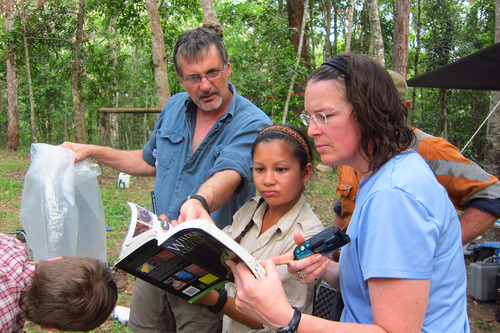

The following afternoon, there was time to collect data from the hapless beast.

For starters, the species had to be determined, as there are two similar ones in the region (Acanthophis antarcticus and Acanthophis praelongus I think), distinguishable only by counting the number of scales ringing the snake’s body.

So, make sure the head is accounted for, and count!

Um, one more time.

So, one species has 19-22 scales in a ring, and the other has 21-24. This one has 21. It’s a toss-up. Write down some other relevant information for posterity.

The bright yellow at the end of the tail is used as a lure to entice geckos, the death adder’s normal prey, close enough for Elapidae work.

And then we say good-bye and ceremoniously march the asp back whence he came.

Steve, not in OSHA approved snake-releasing attire, places the adder next to a cosy dead tree.

Nature-nerd papparazzi ready for a good shoot.

Subject seeking safety from the flashing mob.

The coiled position and flattened body are a warning that we should back off. George’s lens was mere centimeters away from the snake’s nose at this point. No harm was done to any living thing in the making of this photo documentary. Everyone (including the snake) emerged unscathed.