I’m taking on the challenge of trying to encapsulate a week in one blog post. And to add a degree of difficulty, I’m writing this post hoc, three weeks after the fact and from my desk at home in the US of A. Let me know how I do!

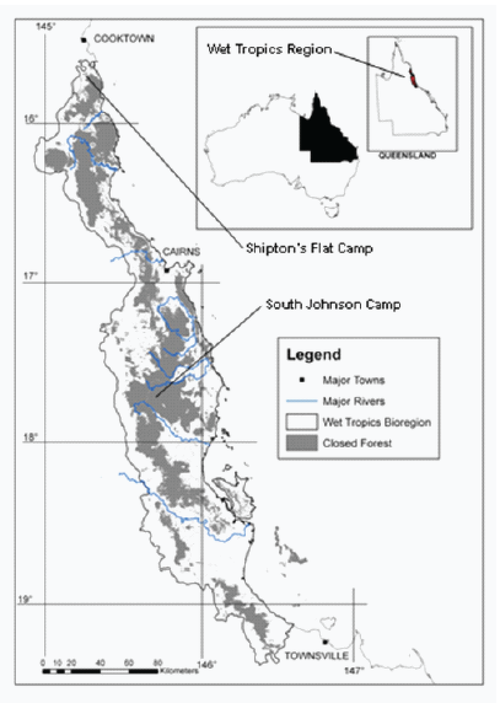

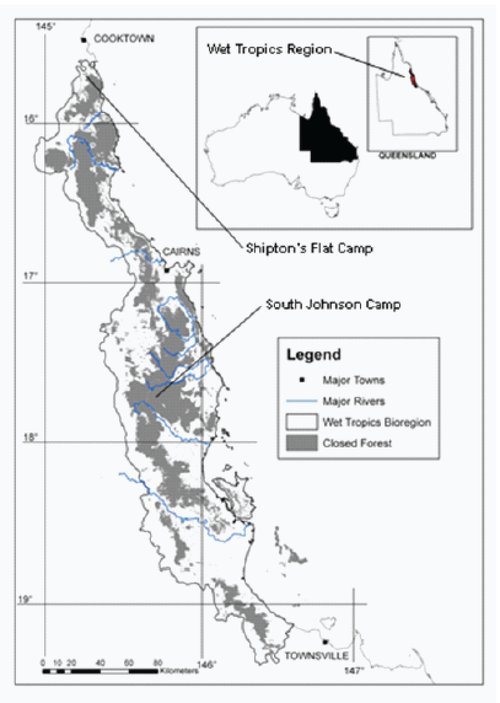

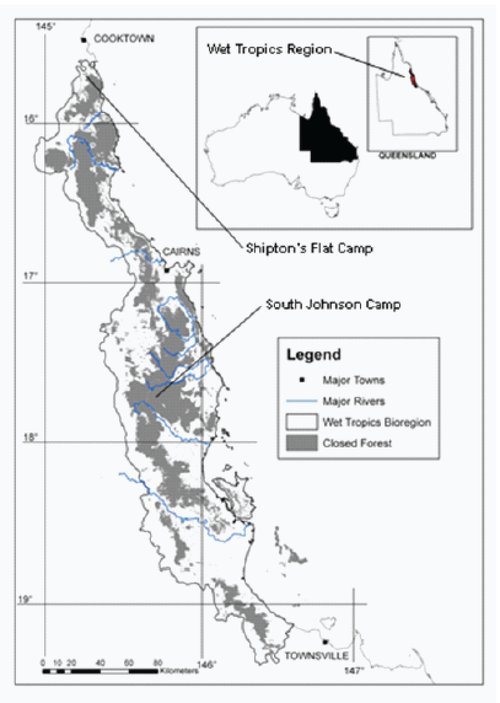

This is an account of the first week of my Earthwatch Expedition investigating the impact of climate change on the vertebrate populations of the wet tropics of northern Queensland.

Sign at South Johnson camp.

We camped at Johnson Creek, a few hundred meters from a wonderful swimming hole (soap-less bathtub), and including two composting outhouses with real seats, walls, a roof, and doors, a building with piped-in river water that served as our kitchen, and two picnic tables with roofs erected above them. It was luxurious, by “really roughing it” standards. Mine is the green tent on the right.

This is the view through the door of my tent.

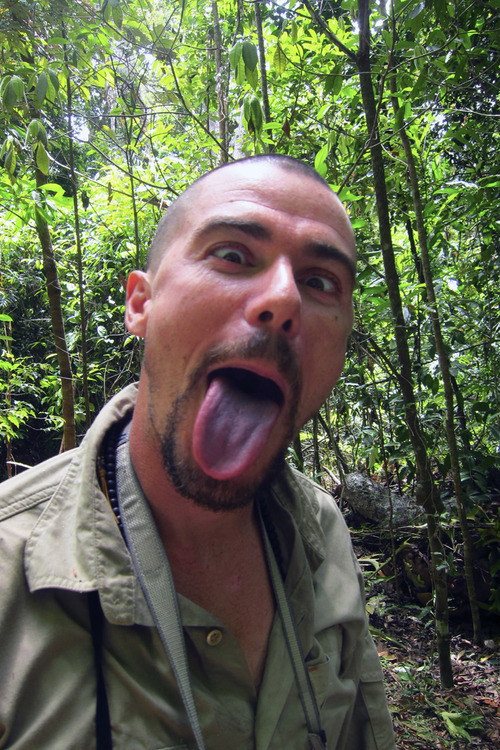

It rains a lot in the Misty Mountains, and it is close to the equator and warm. Consequently, there is a lot of greenery, and much of it is larger than one might expect. Note the hygrometer hairdo.

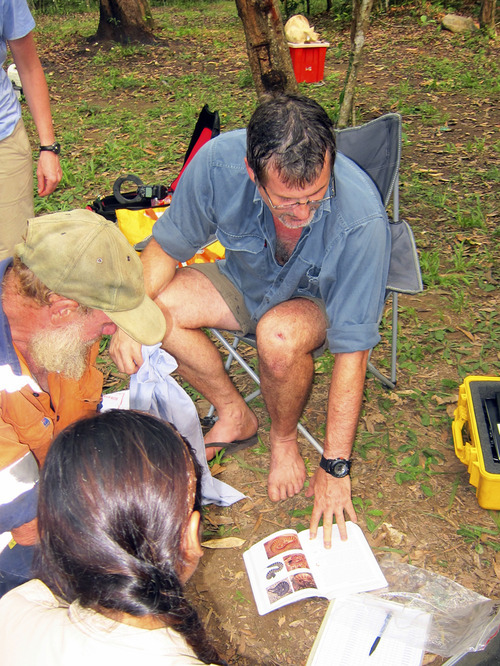

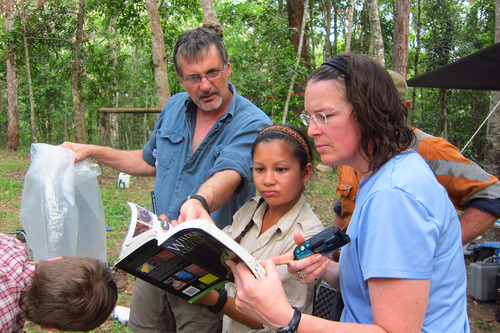

Outside of the kitchen, the research staff erected a big tarp in advance of the arrival of the 8 volunteers, and set up tables to serve as our dining room and office. Here we are in appropriate work attire. (Kate and Danny - there is a legitimate purpose for the subject matter at hand. Admit it!)

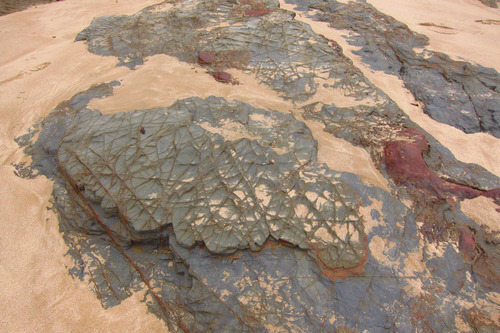

The first evening on site we received an overview of the research, and a safety briefing. In addition to the terrestrial leeches and ticks to which I had been introduced on the koala study, Steve Williams, our unflappable PI (who included a photo of a leech in someone’s eye, among other delightful illustrations to the briefing) talked about venomous spiders, deadly snakes, “merely painful” bites from assorted reptiles, and the most pervasive threat to our health and well-being, plants-to-watch-out-for. Below is a photograph of a stinging tree, Dendrocnide moroides. The leaves are covered with miniscule silicon needles which contain a highly irritating neurotoxin. If one brushes up against the leaves, the hairs break off and bring the toxin with them, They can penetrate lightweight clothing, not to mention bare skin, and the intensely excruciating irritation can remain painful for days, weeks, or months. We all got exceptionally good at recognizing this plant, whether it was a 10cm tall shrublet, or 3m tree. Only two people were stung in the two week expedition, and neither over an extensive area of their bodies. Wax strips, such as those used as a depilatory, help remove the glass hairs. Their availability in our camp first aid kit was much appreciated. Swimming (i.e. cold water) apparently makes the pain worse. As noted by the signs of hebivory, there are critters out there that think stinging trees make good eating. Yet another fact in support of my contention that Australia is just plain weird!

In general, the daily game plan remained the same for both weeks (both locations) of the expedition. Some time before dawn, a subset of the team would get up, eat breakfast, and depart camp to go birding at one of the five elevations where a 1km (in length) transect had been laid out as the sampling site for data collection over a multi-year time frame. The 200m transect abutted the campsite, while 400m, 600m, 800m, and 1000m were at some distance away, so depening on the day, the designated bird brains would walk or drive so as to be on site by 6AM sunrise. The sun really does act like a switch, and though it still feels fairly dark to us humans, the coming light activates myriad avifauna, and a few tweets turns into a cocophany of calls, squawks, songs (mostly songs) in a matter of moments. Alex (“Doctor” Anderson received his PhD diploma from James Cook University a few days after this photo was taken) is a masterbirder (read that carefully) and I witnessed him distinguish and identify as many as 37 different species’ calls at a time. The remarkable thing was, he could imitate each sufficiently well that I was able to then hear what he heard when I listened hard enough.

The string Carolyn is trailing in the photo below (with Alex) measures the distance walked along the transect during the 30 minutes in which data is collected. This is done three times, at three different starting points (e.g. 200m, 400m, 600m distance from the transect start point) each morning. In the course of the week, transects at each of the five elevations were sampled once. Steve’s group (grad students, psot-docs, other Earthwatch teams) will visit each site about 6 times a year, and have done so for 10 years. The data set is quite robust.

Sometimes we saw evidence of birds, but not the birds themselves. This, and a footprint I didn’t photograph, are proof that a cassowary walked this way. At least 80 species of rainforest plants are dependent on cassowaries to distribute their seeds through their poo. When this picture was taken, I had not yet seen a cassowary in the flesh, but I could sense the size of the beast. And they deposit such colorful scat!

This is the first of many photos of impenetrable jungle which we were nonetheless required to penetrate to collect various forms of data.

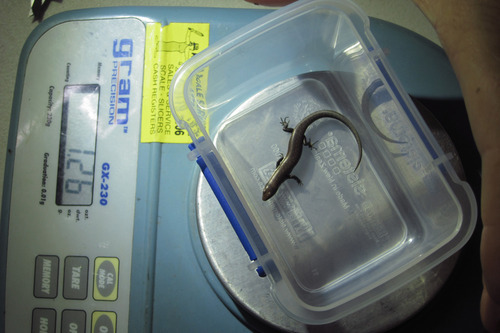

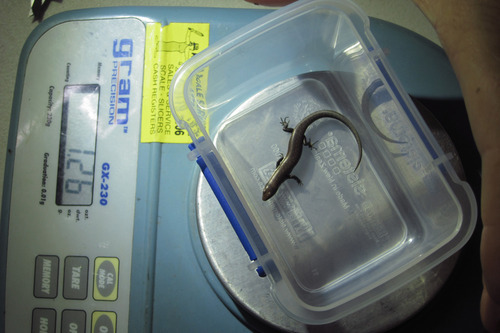

When we returned from birding, we would have “second breakfast,” and regroup to do reptile transects. All of the aforementioned transects served for all types of data collection, but we did not usually visit the same transects on the same day for birds, reptiles, and night-time spotlighting. While snakes, tree dragons, an other large lizards were fair game, the most abundant reptiles were several species of tiny skinks that inhabit the leaf litter of the rain forest (Carlia rubrigularis, Saproscincus tetradactyla, Gnypetoscincus queenslandiae). While I was a fair spotter, when it came to dropping to the ground and catching the swiftly evasive little critters, I found I rarely had the requisite agility. Fortunately, my cronies on the expedition were mostly half my age, and more adept at grabbing the little buggers.

Carlia rubrigularis

We did not endeavor to nab every little reptile we encountered, but did collect a subset to be measured and massed and made to contribute a tip of tail (which they will regenerate) for DNA analysis.

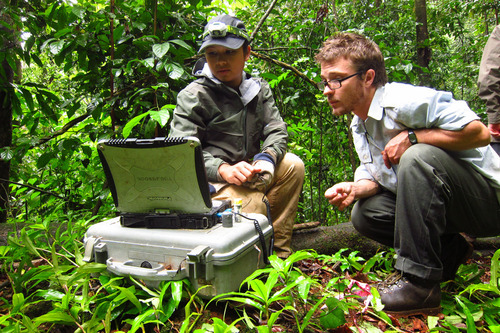

Steve and his fabulous research assistant, Nadiah

Time for Slimfast® for Skinks!

After the reptile transects were dispatched, we returned to camp for lunch, data entry, and a swim/bath/aqua-frisbee frolic in the river. That was followed by dinner preparation (we served as kitchen-help on a rotational basis, or whenever we felt like it) and consumption. The food was varied ample, and delicious, with equally tasty options for the vegetarians in our midst. After dinner, many or most of us went spotlighting, returning again to our various transects to trace the entire kilometer in search of eye-shine from whatever vertebrate species we were lucky enough to see. This included various species of possums high in the trees, dingos if we encountered them, kangaroos and wallabys, native rats (yes, there are placental mammals indiginous to Oz), geckos on tree trunks and on the ground, snakes in logs and on the ground, frogs on trees and atop the leaf litter, fruit bats in the canopy or in flight, and roosting birds. We left the latter alone alone, and their presence was not recorded, but because they were holding still, it helped us neophytes learn what some species actually look like.

This was my first spot on the first night’s outing, a leaf-tailed gecko (Phyllurus cornutus). It’s a lousy photo, but I was happy of myself for seeing something several other people had walked past and not noticed.

We frequently didn’t return to camp until close to midnight or even later, and as some of us were expected to wake up at 5AM for the next day’s birding, we slept fast.

This is a photo of the only member of the group who was older than I. George “of the Jungle” Gornacz, a radiologist/wildlife photographer transplanted decades ago from England, will show up in other photos. His photographic addiction generated the several-times-daily uttered camp refrain “where’s George?” One of the researchers almost ran him over one afternoon when George, dressed in camouflage gear, was lying at the edge of the road with his long lens protruding into the brush. I can’t wait to see the shots he got!!

The locations of each 100 m segmet of each transect is recorded as a GPS coordinate. It is also labelled with lovely pink flagging tape and reflector tape on an easily visible tree by the side of the road or track (pink being visible in both daylight and low light, as it contains pigments reflecting light from both ends of the visible spectrum). Both labels are marked with a 2-letter site designation, a multiple of 100m elevation (e.g. 2, 4, 6…), and the number of meters in along the transect (e.g. 100, 200, 300…). ex. JF2-600 (or something close).

Another vegetatin hazard is called “wait-a-while” Calamus muelleri. The young shoots are allegedly edible, and the vines without thorns are used to make rattan for weaving baskets and furniture. When tromping through the bush, however, the noteworthy features of this plant are the spiky thorns at the base of the sometimes person-high leaf stalks, and the recurved hooks covering the vines that grow from the base of the plant and can reach many meters in all directions. They catch one’s ankles, hair, clothes, and equipment, and force one to yell “wait-a-while” to colleagues as they disappear into the undergrowth ahead of them.

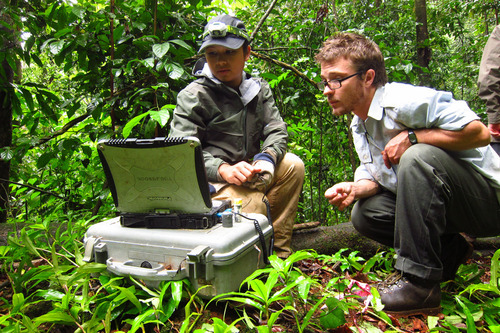

In addition to birds, reptiles, and spotlighting, one afternoon several of us embarked on a “refugia” transect. The refuges alluded to are microhabitats on the south sides of mountains where shade and contour contribute potentially to cooler microhabitats. Given the 3°C global temperature rise predicted in the next several decades, many of the species we were studying will be threatened with extinction. Steve’s belief is that if there are areas that remain significantly cooler, there may be hope for the survival, at least temporarily, of some of the species in the uplands of the Queensland wet tropics. One of his aims is to identify such areas. Instead of surveying for animals in this case, we were looking for the 10 tea strainers that served as housing for data loggers that had been recording temperatures and humidity levels on an hourly or daily basis for many months.

The data from the dataloggers was downloaded on site, and the little double thickness watch batteries (or so they appeared) were replaced.

Flagging tape “bread crumbs” were tied at strategic places olong the steep slope to aid in the next recovery of the dataloggers. (This is Adrian. You’ll meet him later.)

It was very wet, very muddy, somewhat treacherous work. The bottom of the transect was at the top of a little waterfall. Pretty!! (though you can’t actually see it in this picture.)

Adrian, Steve (the PI) Solome (PhD student) and Nadiah (RA) hanging on for dear life lest they slide down the rocks and over the edge.

The 1000m transect was sufficiently far from basecamp that we packed up the trucks and left at 4AM for a day trip to the site. It was pouring (again) on our arrival, so we set up a temporary kitchen, including the 3-burner propane stove, camp chairs, and a large “Eski” for a table. We ate breakfast, and some people did bird transects (when the rain abated - birds don’t sing when it’s raining) while others of us went exploring.

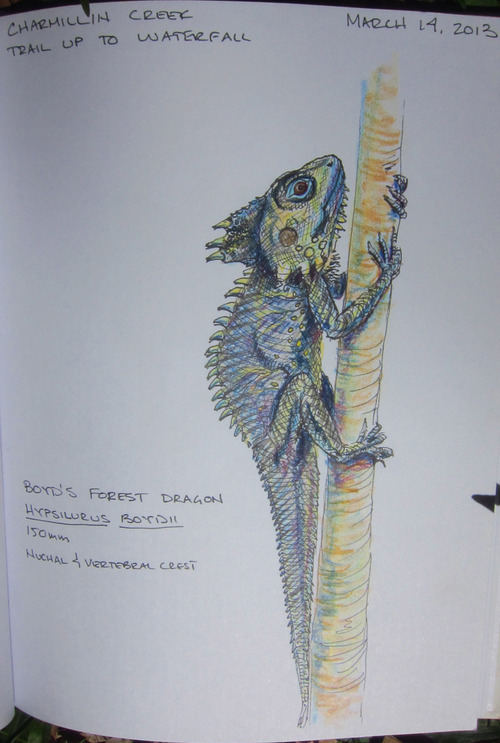

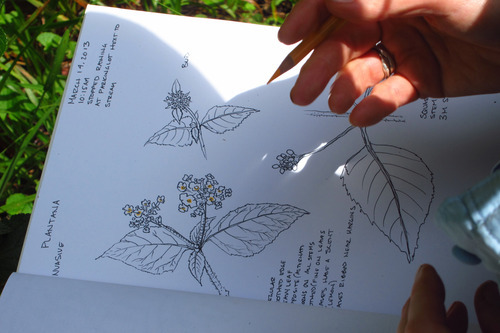

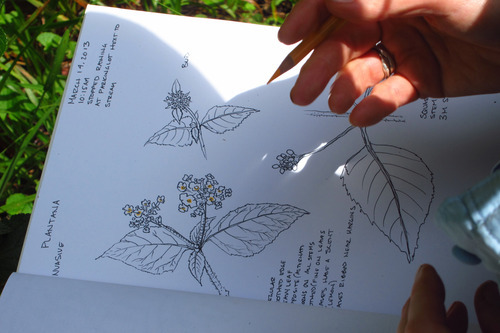

Carolyn Nichols, from Brunswick Maine, is trained as both a scientific illustrator and a biologist. She used every free moment to sketch. I want a copy of her journal!!!!

What Carolyn was drawing. This is lantana, which is beautiful, and some of you may have it in your gardens. Its a genus native to South America that has been introduced and become extremely invasive in Australia. (The Aboriginies who own the land where we camped and worked in the second week of the expedition, have undertaken major eradication efforts in that region.) Carolyn didn’t know it was a bad guy when she started drawing it. She also didn’t know there was a 2 meter red-bellied black snake watching her. She eventually figured that out, and drew him, too.

As usual, we had lunch and looked for reptiles, then packed up for a trip to Millsfalls and a picnic before heading back to base camp. There were lots of way-too friendly kookaburras, but alas, my camera crapped out and I have photos of none of this. I will append pictures from my colleagues when I receive them from Earthwatch.

Until then, here are some more shots from the week:

This itty bitty mushroom couldn’t help but catch my eye.

Bass fiddlehead.

Funky fungi. Lots of the fungi in this area are phophorescent. Is anyone going to ask me how I found that out?

There are lots of species of figs (Ficus) all over Australia, but they are not the only trees with butressed roots. It seems to be a highly addaptive growth habit when things are apt to crawl up your trunk and potentially weight you down in an asymmetric way. This is a relatively small tree, a species of Acacia, I think.

Teeeeeeny weeny mushrooms.

The day before we left dawned and remained clear enough that we could hang things out to dry, including tent flies and towels.

And that led to a clear night, and a sky full of stars. The next day was a trip up to Cairns, showers, beds, pizza, and a day off!

Number of nights in a tent: 12

Number of nights in a tent: 12